Broomberg & Chanarin

The interview with Broomberg & Chanarin was realised by Monica Poggi on the occasion of their solo show at Lisson Gallery in Milan in January 2017.

MP: The media and visual hype that we are currently subjected to is leading us to a fast – and qualitatively terrible – consumption of images. The starting point of your artistic career was the collaboration for Colors, an interesting attempt of organising this huge flux of information and, simultaneously, to celebrate its diversity of perspectives. To what extent did working for the magazine affect your following research?

B&C: Neither of us went to art school, so that moment was our first exposure to the possible use and misuse of images. It was an interesting time. The internet was just emerging. Images were still chosen by transparencies being sent to us by agencies around the world. Most sources came from first-hand interviews. But even in such a measured environment there was a discomfort we felt working around the ethics of image production and dissemination, especially since the magazine was funded by a multi-national. Ultimately, nothing we did could be that critical given its platform.

The common thread among all the works that will be exposed at your first solo show at Lisson Gallery in Milan is a question on the mechanisms that govern representation. Assuming an investigative approach, which culminates in a collaboration with a team of scientists in Trace Evidence, you research what Magritte defined ‘the treachery of images.’ Can photography, in your opinion, still have a testimonial value? Or should we look at it with caution and suspect, as a tool used by institutions that hold the power?

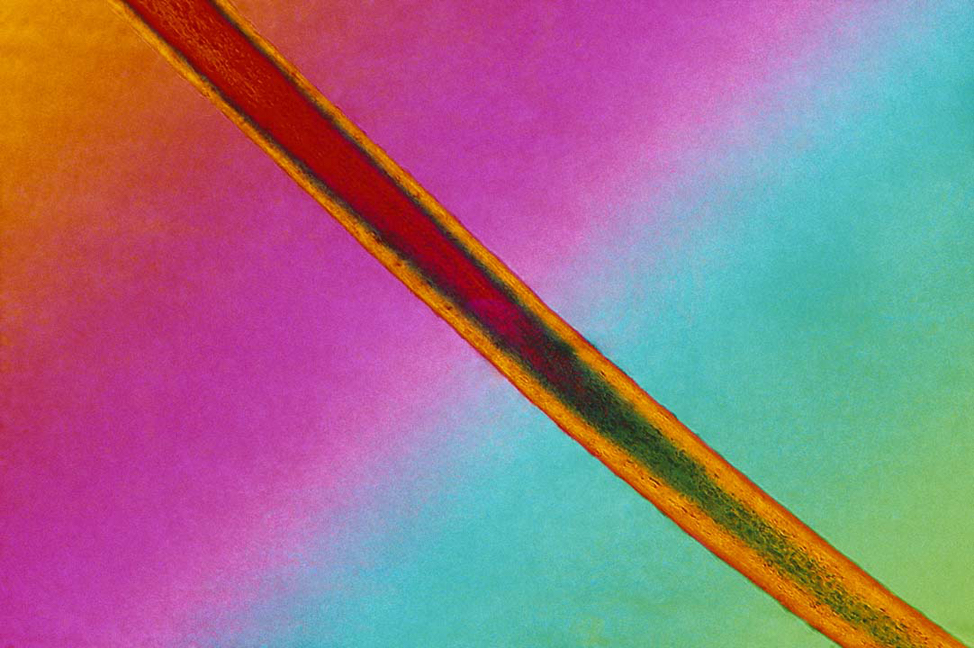

Photographs always have some indexical and occasionally even a testimonial value but as you say the are always complicit with some form of institutional power. The trick is to learn how to exploit their slippery and unfaithful nature. There’s something more whacked out about the show that your description doesn’t allow for. In one small room you have blocks, threads and pixels all of bright and lurid colours stolen from a conflict-zone in Afghanistan, Freud’s couch in London, a bone expelled by a retreating glacier in Switzerland and a Rorschach test from a psychiatric hospital in Cuba. I’m not sure we can sum-up what that ‘common thread’ is that links them all, but the fact that such intense and contrasting historical moments can all occupy one space and make some sense is remarkable.

In his Images in Spite of All, Georges Didi-Huberman defined the underexposed images of the gas chambers taken by prisoners in Birkenau as the existential condition of photography itself; even if they are not providing any information, these pictures indicate the extremely dangerous and urgent state in which they were taken. Could The Day Nobody Died be considered a form of ‘pure’ testimony?

Huberman talks about the act or attempt to make those images as so important. Perhaps its the same with The Day Nobody Died. The absurd and irresponsible performance of creating the work is what makes it so alive and prescient.

In Portable Monuments, you tried to deconstruct the images taken from the media into a visual code that answers to a series of questions by using coloured blocks. How did you create this project and what is its meaning?

Each work is the result of a workshop made in different countries with a group of us all looking at the image on the cover of that days newspaper. The group invents the code by coming up with an interrogation of the image, such as: What is the distance between the camera and the action? What is the resolution of the image? Is the image made with the protagonist permission or not? Is the image made by a professional or civilian? Is the violence implied or explicit? and so on and on and on…. Ultimately, its a tool to provoke a thorough interrogation of images. To spread a mistrust that we have always felt. The blocks are also fun to play with.

–

Broomberg & Chanarin

Adam Broomberg (Johannesburg, 1970) and Oliver Chanarin (London, 1971) live and work in London. Towards the end of the Nineties, they started collaborating as photographers and creative directors of the magazine Colors, produced by Benetton. Both characterised by a strong interest for anthropological and political topics, and on the extent to which media influence perception, they distanced themselves progressively from documentary photography towards a more complex language. Their work insect the ambiguity of images, and the relationship between photography and power. They participated in solo and group shows around the world, and were also awarded of several prizes, such as Deutsche Börse Photography Prize (2013) and ICP Infinity Award (2014).

Image: Broomberg & Chanarin, Trace Fiber from Freud’s couch under crossed polars with Quartz wedge compensator (#3), 2015.

© Broomberg & Chanarin 2015. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Click here to read Monica Poggi’s Work in Focus on Broomberg & Chanarin.

08/02/2017