Through the Looking Glass

(English text below)

Critic essay by Marcella Manni, for the exhibition ‘Through the Looking Glass‘, with works by Martina della Valle, Annabel Elgar and Baerbel Reinhard. (until June 4th in Metronom).

“… she began looking about, and noticed that what could be seen from the old room was quite common and uninteresting, but that all the rest was as different as possible. For instance, the pictures on the wall next the fire seemed to be all alive…”

Paul Klee, as early as 1924, pointed out that first of all it is not we that approach images but images that turn their glance upon us and may therefore be considered an active subject. To speak, write and reflect on the life of images, at least in western culture, even limited to the last century, one must take for granted many studies, many viewpoints, transversal to philosophy and the history of art. In the context of the micro-cosmos of works presented by the exhibition Through the Looking Glass, the images may undoubtedly be considered by setting out from Aby Warburg’s insight “you live and do nothing”.

In trying to take a further step, it is worthwhile referring to the quality of fiction: it is no accident that Alice’s favourite words (through the looking glass, precisely) are “let’s pretend”. A fiction however that is not defined as being in opposition to reality: the real/simulated pairing does not, at least in reflection on the works of Elgar, della Valle and Reinhard, have any validity if we are talking about a context of images. In fact the contemporary context shows us daily how the virtuality of simulated worlds produces effects and fallouts more than contingent to the real world, and perhaps this is where the further step lies. So what passage do these images cause us to make, what might “through the looking glass” mean? Let us take a step backwards: for Leon Battista Alberti one has an image (simulacrum, to be precise) at the moment when a natural object shows a minimum of human re-elaboration; that is, this condition is satisfied when natural forms with a character that may be defined as iconic (tangles of branches, for example) are re-elaborated with the use of frames and pedestals.

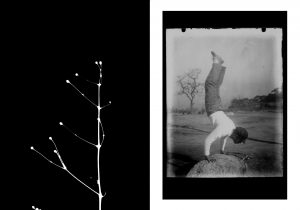

Martina della Valle, Wabi-Sabi #2, 2015

Martina della Valle’s Wabi-Sabi sets out precisely from natural elements, branches, leaves, flowers which find their iconic characteristic in the rendering of the contact print, the equivalent of a frame. Perfectly adhering to nature, the 1:1 scale is respected and they equally adhere to the spiritual values of the ‘beauty of imperfection’: della Valle’s works are ever-changing, impermanent and structurally incomplete. The paradox of the photograph that “fixes” the ongoing and ceaseless transformation of things is subverted here; the completeness, the moment of perfection may be achieved in budding flowers but also in bare branches or a flower arrangement. Beauty, and we might perhaps say art, is thus found in unconventional form: in objects, situations which retain their characteristic familiarity but which are transformed, or better, subverted.

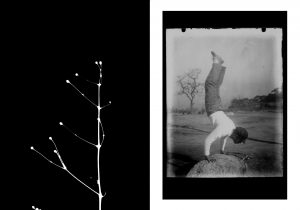

Annabel Elgar, Specimen found in the trophy cupboard of Frosted fly fishing club, 2014

The ephemeral and the concealed are the fulcrum of Annabel Elgar’s series Cheating the Moon: Elgar transforms an object to a material that has the nature of evidence, proof, a sort of research into her own origins. ‘Operation Lunar Eclipse’ is the name of the federal operation begun in the United States in 1998 to combat the sale of fragments of lunar rock, namely the 270 moon rocks (from the Apollo missions) which were given as gifts to various governments of the world during the Nixon administration. Constructing a variant of undercover inquiry, Elgar creates a kind of map of potential findings of the dispersed moon rocks, with precise and carefully studied details. The images at once reveal and conceal details of the story, playing on the positive ambiguity of the concept of fiction understood as a tool of creation and unveiling of the images at one and the same time. Moon dust forms a mountain range, a rock becomes the subject of study in a kirigami workshop, ending up under the lens of an amateur researcher. In Elgar’s work the image plays a peculiar role in a cultural environment that goes beyond a solely representative capacity. Nature and culture, to which is added technology, almost duty-bound.

Baerbel Reinhard, Senza titolo, 2015

Baerbel Reinhard creates works that are openly technologically built: the experiment carried out is one that interweaves what our senses receive, in this case the glance that records portions of landscape, and the constructional option of the image. Elaboration is both materially the physical overlapping of images and selection of portions thereof, and intellectually level, the choice of which landscapes to combine and superimpose. Punctum is the synthesis of this procedure, a minimal sign in the graphic formulation but powerful and absolute with regard to pertinences.

Heimat, a concept as familiar to German culture as wabi-sabi is to Japanese, shares the same absence of univocal definition in linguistic terms and is the synthesis, almost the performative dimension of the image. Like Lacan’s sardine tin that glitters in the sun of a beach, its ‘undulation’ in the sunlight is the symbol of the ability of images to attract our gaze, of their being much more than simple ‘things’. What then does one find (and seek) in going through the looking glass, according to Elgar, della Valle and Reinhard (as perhaps for Alice)? Ambiguity, contradiction and multiplicity, certainly not resemblance or identity. In a world where the role of images is accepted as dominant, the images themselves constitute a cultural environment to analyse in its capacity to provoke ‘disorder’ in the world.

ENG:

Critic essay by Marcella Manni, for the exhibition ‘Through the Looking Glass‘, with works by Martina della Valle, Annabel Elgar and Baerbel Reinhard. (until June 4th in Metronom).

“… she began looking about, and noticed that what could be seen from the old room was quite common and uninteresting, but that all the rest was as different as possible. For instance, the pictures on the wall next the fire seemed to be all alive…”

Paul Klee, as early as 1924, pointed out that first of all it is not we that approach images but images that turn their glance upon us and may therefore be considered an active subject. To speak, write and reflect on the life of images, at least in western culture, even limited to the last century, one must take for granted many studies, many viewpoints, transversal to philosophy and the history of art. In the context of the micro-cosmos of works presented by the exhibition Through the Looking Glass, the images may undoubtedly be considered by setting out from Aby Warburg’s insight “you live and do nothing”.

In trying to take a further step, it is worthwhile referring to the quality of fiction: it is no accident that Alice’s favourite words (through the looking glass, precisely) are “let’s pretend”. A fiction however that is not defined as being in opposition to reality: the real/simulated pairing does not, at least in reflection on the works of Elgar, della Valle and Reinhard, have any validity if we are talking about a context of images. In fact the contemporary context shows us daily how the virtuality of simulated worlds produces effects and fallouts more than contingent to the real world, and perhaps this is where the further step lies. So what passage do these images cause us to make, what might “through the looking glass” mean? Let us take a step backwards: for Leon Battista Alberti one has an image (simulacrum, to be precise) at the moment when a natural object shows a minimum of human re-elaboration; that is, this condition is satisfied when natural forms with a character that may be defined as iconic (tangles of branches, for example) are re-elaborated with the use of frames and pedestals.

Martina della Valle, Wabi-Sabi #2, 2015

Martina della Valle’s Wabi-Sabi sets out precisely from natural elements, branches, leaves, flowers which find their iconic characteristic in the rendering of the contact print, the equivalent of a frame. Perfectly adhering to nature, the 1:1 scale is respected and they equally adhere to the spiritual values of the ‘beauty of imperfection’: della Valle’s works are ever-changing, impermanent and structurally incomplete. The paradox of the photograph that “fixes” the ongoing and ceaseless transformation of things is subverted here; the completeness, the moment of perfection may be achieved in budding flowers but also in bare branches or a flower arrangement. Beauty, and we might perhaps say art, is thus found in unconventional form: in objects, situations which retain their characteristic familiarity but which are transformed, or better, subverted.

Annabel Elgar, Specimen found in the trophy cupboard of Frosted fly fishing club, 2014

The ephemeral and the concealed are the fulcrum of Annabel Elgar’s series Cheating the Moon: Elgar transforms an object to a material that has the nature of evidence, proof, a sort of research into her own origins. ‘Operation Lunar Eclipse’ is the name of the federal operation begun in the United States in 1998 to combat the sale of fragments of lunar rock, namely the 270 moon rocks (from the Apollo missions) which were given as gifts to various governments of the world during the Nixon administration. Constructing a variant of undercover inquiry, Elgar creates a kind of map of potential findings of the dispersed moon rocks, with precise and carefully studied details. The images at once reveal and conceal details of the story, playing on the positive ambiguity of the concept of fiction understood as a tool of creation and unveiling of the images at one and the same time. Moon dust forms a mountain range, a rock becomes the subject of study in a kirigami workshop, ending up under the lens of an amateur researcher. In Elgar’s work the image plays a peculiar role in a cultural environment that goes beyond a solely representative capacity. Nature and culture, to which is added technology, almost duty-bound.

Baerbel Reinhard, Senza titolo, 2015

Baerbel Reinhard creates works that are openly technologically built: the experiment carried out is one that interweaves what our senses receive, in this case the glance that records portions of landscape, and the constructional option of the image. Elaboration is both materially the physical overlapping of images and selection of portions thereof, and intellectually level, the choice of which landscapes to combine and superimpose. Punctum is the synthesis of this procedure, a minimal sign in the graphic formulation but powerful and absolute with regard to pertinences.

Heimat, a concept as familiar to German culture as wabi-sabi is to Japanese, shares the same absence of univocal definition in linguistic terms and is the synthesis, almost the performative dimension of the image. Like Lacan’s sardine tin that glitters in the sun of a beach, its ‘undulation’ in the sunlight is the symbol of the ability of images to attract our gaze, of their being much more than simple ‘things’. What then does one find (and seek) in going through the looking glass, according to Elgar, della Valle and Reinhard (as perhaps for Alice)? Ambiguity, contradiction and multiplicity, certainly not resemblance or identity. In a world where the role of images is accepted as dominant, the images themselves constitute a cultural environment to analyse in its capacity to provoke ‘disorder’ in the world.

works by Martina della Valle, Annabel Elgar, Barbel Reinhard

until June, 4th 2016

Metronom, viale Amendola 142 – MODENA