MILO KELLER

Generazione Critica: Since 2012 you have been heading the photography department at ECAL / Ecole cantonale d’art de Lausanne, before becoming a teacher at this school you were also a student, how has the school changed and how has the course of study for photography students evolved?

Milo Keller: For twenty years we have been living and participating in a photographic revolution. I began my studies at the ECAL / Ecole cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ecal.ch / @ecal_photography) at the beginning of the new millennium. The classics that we were reading was: “La Chambre Claire” by Barthes, “On Photography” by Sontag and “Ways of seeing” by Berger. In the beginning, we worked with analog cameras and spent long hours in the reddish half-light of the black and white laboratory or, for color prints, in total darkness. It was a chemical and physical work, accompanied by heavy infrastructures: cameras, easels, lights. By the 1990s, photography had begun its inexorable conversion to digital arriving to be incredibly malleable, particularly thanks to a new program: Photoshop. During my years of studies, the techniques quickly evolved towards hybridization: analog shots then film scanning, digital retouching and inkjet prints. The lighting technique was mainly flash: an almost magical light source, very powerful and practically imperceptible to the naked eye. Stylistically we were influenced by the Düsseldorf school and by the famous pupils of the Becher: Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Candida Höfer and Andreas Gursky. Commercial photography was still linked to printed magazines that had great media and circulation and in fashion, of which the questionable porno-chic characterized aesthetic and content canons.

Then the photographic image began to be an image on the net (network image) first on the internet and, since 2004 with Facebook also on social networks. Fewer films, fewer prints, fewer magazines for an avalanche of more digital images. Cameras have turned into video cameras and photographers have become filmmakers. Today, photographic images are often composite visions (made up of a multitude of images), resulting from invisible algorithmic operations that automatically construct a representation of reality. ECAL is a school that does not like academics, teachers are first of all professionals: artists and commercial photographers willing to connect teaching to practice, to their profession. To keep up with the times, part of the course contents are constantly changing: we adapt to technologies that are quickly overtaken by new ones, we study new markets trying to identify their artistic and commercial perspectives and we read other authors such as Vilém Flusser with “Towards a Philosophy of Photography” or James Bridle with “The new Dark Age”.

©Milo Keller, Le Corbusier – notre dame du haut, courtesy the artist

GC: Your position as a teacher gives to you an observatory and a generational exchange context that can be consider privileged. How does this experience affect your research and your practice as a photographer?

MK: I certainly enjoy a privileged situation, fueled by constant conversation not only with teachers but also with students and assistants. Often the push for change comes “from below” from needs and issues that the new hyper-connected generations experience firsthand and that they wish to elaborate during their studies. Younger teachers are “naturally” tuned to the needs of students while the more experienced ones benefit from a critical distance necessary to understand passing phenomena, cyclical issues and epochal changes. On a technical level, I try to be always up-to-date: if I used the optical bench a lot as a student, today I work with a phaseone camera (medium digital format), I fly with a drone and I use the new filters based on the artificial intelligence of Photoshop 22. Besides technological evolution, in my photographic practice I remain faithful to a minimal vision obtained through the distillation of ideas and forms not for lack of tools, but for choice.

GC: Analogue and digital, what significance has this dichotomy assumed today? Is it still a dichotomy?

MK: Who still shoots analog? Some artists and some enthusiasts including my students.

I don’t think it’s more pertinent to talk about the dichotomy between analog and digital as digital photography dominates all sectors from commercial to artistic production processes. Let’s look around us, the turning point has happened: Kodak has gone bankrupt and there is no turning back. Nonetheless, at ECAL we continue to believe in the plastic and pedagogical value of film and still teach our students to work with an optical bench, to develop black and white films and prints. Physical understanding of photographic processes allows for a better understanding of their digital translation. It is also a question of pleasure for a manual skill that still continues to fascinate the youngest and which takes precedence in a dematerialized world. The new dichotomy is to be found between the real and the virtual where the photo-realistic images of non-existent scenes intertwine (and merge) in our visual experience. This is the dichotomy at the origin of my research projects.

GC: You recently started “Augmented Photography”: a research project focused on the issue of materialization and de-materialization of the photographic image. How does it develop and what kind of actions has it put in place? Do you believe that the pandemic condition has accelerated the relevance of this debate or was it a trend already underway?

MK: “Augmented Photography” is a completed research that was started in 2016 together with the new Master in Photography that I developed for ECAL. The project made it possible to give an identity and a program to the new master by forging its contents. The research was divided into two directions: the materialization of photography in a sculptural form or in installation and the de-materialization of photography as a direct consequence of its digitization. The tension between matter and numerical data has manifested itself in opposing trends: on one hand the art market which (before NFTs) wanted unique, exclusive and physical objects and on the other the commercial pressure mainly operated by Silicon Valley for the large-scale diffusion of images on the net. These market realities were among the starting points to work in an experimental and practical way on the creative possibilities offered by the “new” technologies while a more theoretical reflection was elaborating projections on the becoming of photography.

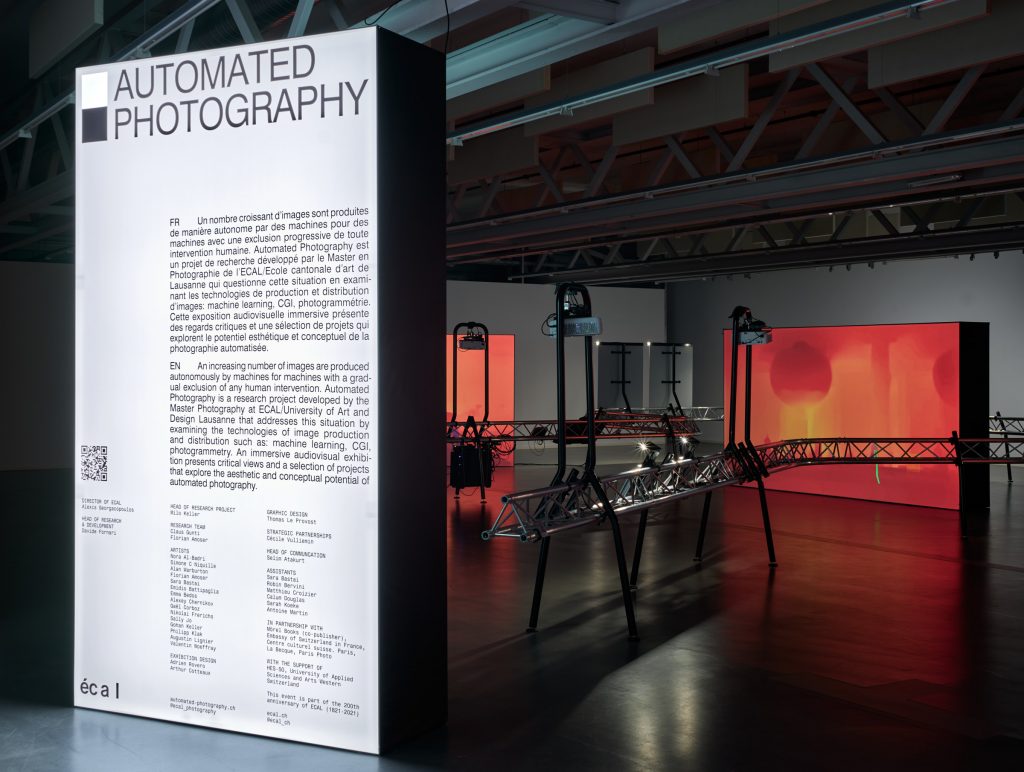

From the first research project, and considering that today most of the images are produced by machines for other machines without any human intervention, we have launched a second program: “Automated Photography” (automatedphotography.ch) which analyzes the automatic processes in production and distribution of photographic images. On a practical level, we explored the creative potential of technologies such as photogrammetry, drones, LIDAR, and some Artificial Intelligence applications. On the theoretical level, we discussed the social, political and economic tensions of a system that generates images that tends to escape from our direct control.

The pandemic condition has certainly accelerated the development of remote communication technologies capable of bringing home streaming of work, education and even more than before, personalized entertainment. This situation has highlighted the importance (and monopoly) of industries that offer “free” services by capitalizing on our attention and our time (“attention economy”).

©Automated Photography, Elac Lausanne, courtesy ECAL/Florian Amoser

GC: Augmented reality, virtual reality, photogrammetry, CGI, the scenario of using images is more than expanding and changing. More and more often the term ‘image economy’ is used in referment to a transversal and broad scope of skills and use, which also includes the one of the visual arts. From a production point of view, what kind of skills are needed to move consciously and professionally in this context?

MK: Indeed, there is an interesting convergence between photographic images that have different natures but a common cultural background. A first group is based on the traditional photographic principle of “writing light” which works on photosensitive surface such as an analog film or a digital chip. On the other hand, there are artificial photographic images created through CGI (Computer Generated Imagery) programs such as Blender or Cinema4d that simulate the projection and reflection of light sources on subjects created virtually in 3D on the computer. These images have photographic characteristics but they are not real photographs: they are not based on scenes that exist in physical and material reality. The photographic images of the first and second groups are based on the visual culture which is itself a construction based on our history and experience. The economy of the image ranges in forms that may seem distant but have common roots and specific evolutions. Virtual media often reproduce analog functions which are translated into digital form. For example, for 3D creation, software lean on virtual photographic studios and the different possible choices for the light source, on the type of camera used and on the frame, connected to our real experiences. These bonds benefit people who have a classical background in photography who can find similar skills in a digital key.

GC: Graphics, architectural design, computer games but also medicine, is it true that we can say, in a certain sense, that we first think through images? Is this really a cultural revolution?

MK: Babies first see then communicate with sounds and expressions and finally learn to speak. Today communication is dominated by images that parade on our smartphones intercepting our attention and our visual instincts. The images know no language barriers but are subject to polysemic and sometimes ambiguous readings with respect to the culture of production and reception. If writing education is a universal practice, image education often remains a marginal option. It is a paradox of our contemporary condition: we communicate more and more with images but we lack the necessary education to analyze and manage them. The real cultural revolution will take place when the school (starting with elementary ones) will keep up with the times. On that note, I think that written culture is not to be opposed to the visual one but on the contrary it must also be supported and articulated.

© ECAL/Gohan Keller, See me in depth

GC: Digital art is entering, even if in a slow and episodic way, the sphere of interest of institutions and museums, traditionally dedicated to photography. I am thinking of two virtuous examples, the Fotomuseum in Winterthur or the Media Wall of the Photographers’ Gallery in London. Is it becoming more and more necessary to think of a different paradigm of cultural management and planning that knows how to competently interpret areas that at the same time are both similar and distant?

MK: Fortunately, there are courageous institutions such as the Fotomuseum in Winterthur, the Photographer’s gallery in London, FOAM in Amsterdam and the C / O Berlin that are capable of combining more traditional photographic forms with new digital proposals. My interlocutors work in these museums, my adventure community ready to explore the boundaries of photography by embracing new dimensions. This progressive opening is necessary not in a vision of rupture with the past but for searching a continuity of intergenerational exchange.

GC: Design and architecture, how much does photography play a priority role today in the generation of images as ‘applied art’? How much of study cab be found in your research?

MK: Photography has always played a double game, its ambiguity allows to consider photography as an applied art and as a free expression in visual art. Its technicality, its reproducibility excluded it for a long time from the “visual arts” allowing it to achieve commercial success. The focus of my activities is mainly on teaching and research for ECAL but I continue to carry out rare “applied art” projects for fellow designers and architects who share a common vision.

GC: Arnheim entrusts to artists with the roke of inventor, builder and judge; the final result, the art work, is identified as the result of a thought process. Can an analysis of the image that also includes the way in which images are viewed lead to a less stereotyped and instrumental vision of the work of the artist, designer or graphic designer?

MK: The images are objects of mediation between the artists (applied and not) and the public. This relationship can develop emotionally and intuitively or on more intellectual levels. Some images are unique, others more layered and complex. The same photograph can be seen on the surface and analyzed in depth. Most of the photographic images are functional without depth and without history with limited usefulness for a specific time. As with our cognitive system that works with short and long-term memory, certain images are imprinted on our consciousness and others disappear in the unstoppable visual flow. Today, many are wondering if Artificial Intelligence can replace us inside the more complex creative processes that, following the words of Arnheim, involve the invention, construction and judgment of images. For now, on a visual level, this type of intelligence remains mechanical and sterile: it learns to produce “new” images by analyzing image banks produced by humans. The autonomous artificial intelligence capable of producing a new style, a complex concept, a synaesthesia has not yet been born. The opportunities today are to be found in the collaboration between the machines and us. Maybe it’s just a matter of time, maybe it’s a vain hope but for now the authors are graphic designers, photographers, designers and artists who still have the privilege of subjectivity.

Milo Keller (1979, Lugano, Switzerland), photographer and professor, is known for his photography works in the field of architecture and design. Since 2007, he has been teaching at ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne. Since 2012, Keller has curated numerous exhibitions and publications in Switzerland and internationally while offering conferences on his pedagogical and research activities in the fields of Computer-Generated Imagery, Augmented and Virtual Reality, Photogrammetry and A.I.

© Copyrights Metronom

10/03/2022